Aldo Leopold Legacy Center

Project Overview

Published in 1949 as the finale to A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold's "Land Ethic" set the stage for the modern conservation movement. Leopold's philosophy included the belief that the idea of community should be enlarged to include, in his words, "collectively: the land." This includes nonhuman elements such as soils, waters, plants, and animals.

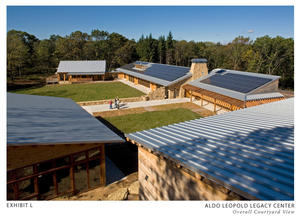

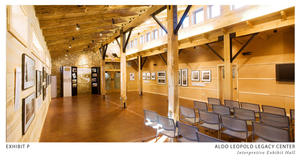

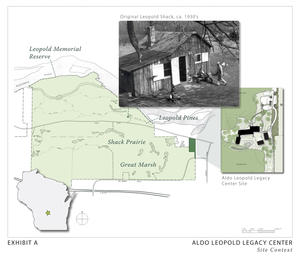

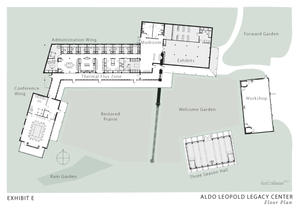

The headquarters for the Aldo Leopold Foundation, the Legacy Center includes office and meeting spaces, an interpretive hall, an archive, and a workshop organized around a central courtyard. Built where Leopold died fighting a brush fire in 1948, the Legacy Center also provides a trailhead to the original Leopold Shack.

Design & Innovation

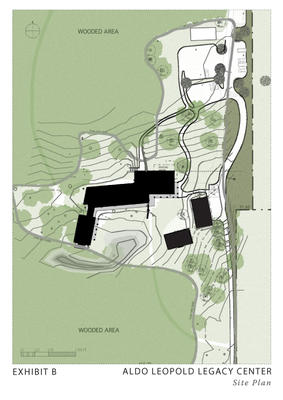

The Foundation located the project on a previously disturbed site, which it is restoring to native ecosystems. The project team used crushed gravel in place of blacktop or concrete paving, increasing rainwater infiltration and blending the developed areas into the surrounding landscape.

The native landscaping requires no irrigation. Waterless urinals, dual-flush toilets, and efficient faucets reduce water consumption by 65%. An on-site well provides potable water, and an existing septic system treats wastewater.

Thinning the Leopold forests improved forest health while providing 90,000 board feet of wood for use in the project. More than 75% of all wood used in the project was certified to Forest Stewardship Council standards, and 60% of all materials were manufactured within 500 miles of the project site.

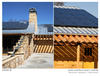

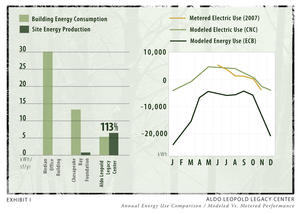

The Legacy Center was designed to use 70% less energy than a comparable conventional building. A 39.6-kW rooftop photovoltaic array produces more than 110% of the project's annual electricity needs. This excess renewable energy, along with on-site carbon sequestration, offsets the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the project's operations.

Daylighting eliminates the need for electric lighting during most of the day. Ground-source heat pumps connected to a radiant slab provide heating and cooling, and an earth-tube system provides tempered fresh air.

Regional/Community Design

The Aldo Leopold Foundation viewed the construction of the Legacy Center as an opportunity to continue a 70-year tradition of land stewardship. While the Leopold Shack became a metaphor for living lightly on the land, it is the land itself and the Leopold family’s efforts to restore it that truly informed and inspired Leopold’s observations and writing.

The Legacy Center was built on a previously disturbed site that reinforces the historic connection to the Shack and marks the location of Leopold’s death. The rural setting is essential to the Foundation's mission, which is to engage people in the process of ethical land management.

Education and community outreach was a central theme of the project: the Foundation held field days during the winter tree harvest, volunteers stripped bark from logs, local craftspeople designed furniture and building details, a local sawmill operator worked on the site, and the Foundation sponsored renewable energy workshops and building tours throughout construction. In its first year of operation, the Legacy Center hosted more than 5,500 visitors.

Most visitors arrive in groups by van or carpool. The parking area was designed to accommodate average, not peak, use. Because the Foundation headquarters moved from the nearby town of Baraboo to a rural area, the project team included staff commuting in the Legacy Center's carbon analysis. The Foundation purchased adjacent real estate to house interns and visiting researchers.

Metrics

Land Use & Site Ecology

As part of restoration efforts during the 1930s and 1940s, the Leopold family planted thousands of trees on their worn-out Sand County farm. Seventy years later, the forested areas on the 1,500-acre Leopold Memorial Reserve were overcrowded, resulting in poor canopy development and an extremely low annual growth rate.

Research determined that careful thinning could improve forest health, increasing carbon sequestration and increasing the potential for the remaining trees to live 150 years. This thinning process provided a raw material for the project and gave the Foundation a way to honor the symbolic importance of the Leopold pines. The quantity and nature of the wood made available from the thinning shaped the building design and provided an example of responsible land management.

The building was located on a previously disturbed site on the Leopold Reserve. As part of a continuing effort, the Foundation is restoring the site perimeter to the appropriate ecological communities of prairie, savanna, and wetland. Collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other organizations make the site a demonstration center for ecological restoration and native landscaping.

All rainwater is managed on site. The site's geology, including more than 300 feet of sand, encourages natural percolation of rainwater. The project team minimized impervious areas by using crushed gravel in lieu of blacktop or concrete paving, increasing rainwater infiltration and blending the developed areas into the surrounding landscape. Rainwater captured from the roof is funneled through an aqueduct into a rain garden planted with native species before it filters back into the aquifer. The team designed parking pockets with shaded areas to reduce the project's contribution to the urban heat-island effect and designed parking areas and roadways to circulate around existing trees.

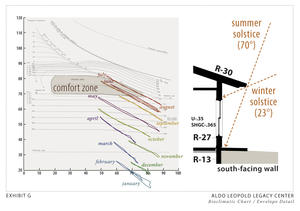

Bioclimatic Design

The project team realized more than half of the project's energy savings through low-tech, high-yield design strategies. The team worked to create a simple, stable building shell that performs quietly and with little mechanical assistance in all seasons. The goal was to make a durable building that balanced energy efficiency with user comfort and ease of operation.

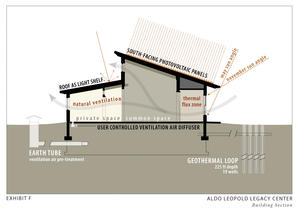

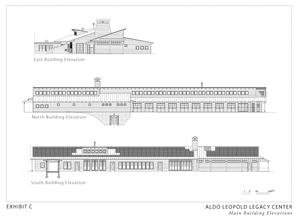

The main building's long, narrow footprint allows for natural ventilation and daylighting. A south-facing, minimally conditioned thermal flux zone provides a buffer to staff areas and allows occupants to manage natural ventilation, solar gain, and glare. Overhangs shield the interior from direct sun in the summer but allow passive solar gain in the winter. The roof maximizes solar electricity production and bounces indirect light into the building, and the building envelope minimizes thermal transfer. Private staff spaces provide acoustical separation from public spaces and allow occupants to control airflow, cooling, and daylighting. The building's ground-source heat-pump system uses the earth as a heat source in the winter and a heat sink in the summer, and the earth-tube system provides fresh, tempered air in all seasons.

Light & Air

The Legacy Center's main building is an all-perimeter space oriented along an east-west axis to maximize daylight penetration and to allow strategic placement of operable windows for cross ventilation and passive heating and cooling. Daylight levels provide sufficient general illumination during most periods of the day. Light enters the building from two directions, providing balanced natural light. All work areas have direct views to the outdoors, and all work stations include task lighting.

The project team selected all adhesives, sealants, paints, and composite-wood products for their low chemical emissions. Displacement ventilation provides fresh air that has been preconditioned by an earth-tube system. An ultraviolet filter located between the earth tubes and the air-handling unit controls mold and bacteria. All building areas except the basement mechanical room can be naturally ventilated in appropriate weather. The radiant floor provides heating in winter and cooling in summer. Staff determine whether the building is operated in natural-ventilation, heating, or cooling mode.

Metrics

Water Cycle

The site does not have a permanent irrigation system. Waterless urinals, dual-flush toilets, and water conserving lavatories reduce water consumption by 65%, compared with a typical building. An on-site well provides potable water, and an existing septic system treats wastewater.

Energy Flows & Energy Future

The Center is designed to maximize number of occupied hours lights and HVAC systems are off. All occupied spaces are daylit and naturally ventilated. With auxiliary wood burning stoves, the building has passive survivability during the day. High enclosure insulation levels and passive solar strategies minimize heating load while optimum shading design minimizes summer solar gains.

The air-handling unit delivers only required ventilation air, reducing fan sizes by 80% compared with typical systems. Displacement ventilation, VFD fans and demand control ventilation reduce energy demand. Ground source water-to-water heat pumps maintain a 500 gallon tank at 110°F in winter and 45°F in summer. Water from the tank is pumped to radiant slabs for space heating and cooling and coils to condition ventilation air.

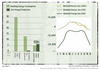

Modeled annual energy demand is 54,229 kWh. A 39.4 kWp photovoltaic array provides 61,250 kWh of electricity. 34,341, kWh is sold to the electric utility and 26,180 kWh is purchased from the utility.

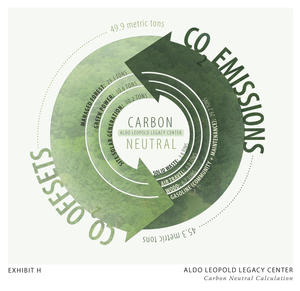

A carbon balance based on WRI Greenhouse Gas Protocols indicates 13.63 Tons Carbon emitted per year, 6.24 Tons Carbon offset and 8.75 Tons Carbon sequestered in managed forests for a net offset/sequestration of 1.36 Tons of Carbon.

Metrics

Materials & Construction

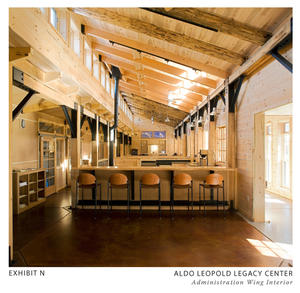

Approximately 90,000 board feet of site-harvested lumber was milled and dried locally for window frames, doors, siding, flooring, paneling, and artisan-crafted furniture. Pine trees were debarked on-site, air-dried, and used to construct innovative round-wood rafters and trusses. Nearly all of the Legacy Center’s timber skeleton was built with Leopold pines. The Leopold Foundation secured Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) chain-of-custody certification for its own wood through the Smartwood certification body. Measured by value, 78% of all wood used in the project is FSC certified.

Materials with recycled content were used throughout the project. The roof includes high levels of recycled aluminum, for example, and the concrete has flyash in place of much of the portland cement. The rainwater aqueduct and fireplace were made of stone reclaimed from an airplane hanger built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. The project team also preferred local and regional materials; interior walls were plastered with local sand, clay, and straw, and 60% of all materials, by cost, were manufactured within 500 miles of the project site.

The Aldo Leopold Foundation used waste pulp from the harvested Leopold pines to print a special edition of A Sand County Almanac on archival-quality paper made through an experimental pulping process that used no chlorine or sulfur.

Long Life, Loose Fit

The Aldo Leopold Legacy Center was designed to last at least 100 years. Every design decision was made with a view toward the long term. The project was designed to fit within its ecological landscape, using materials that will age gracefully over time. The main building's simple, stable shell is constructed of durable materials. The anticipated service lifetime of the aluminum roof exceeds that of other roofing options. Roof overhangs keep water off exterior walls and windows, improving durability.

Leaving the project's structure exposed in interior spaces reduced the need for finish materials, enhancing durability and reducing maintenance needs. Common spaces were designed to be flexible and easy to modify. Office dimensions were kept to a minimum, reducing the ratio of private space to common space. The mechanical room was sized to accommodate maintenance and future retrofits. The use of copper piping in the mechanical room should extend the life of the piping system.

Collective Wisdom & Feedback Loops

Although the availability of Leopold wood presented an extraordinary opportunity unlikely to be repeated in other projects, the process through which the project team engaged in the design of this facility is replicable and holds lessons for the construction of other buildings. The Legacy Center's precedent-setting aspects include the rigorous analysis of its energy use and carbon footprint, its innovative approach to natural ventilation, its extensive use of locally harvested and recycled-content materials, and its small overall ecological footprint.

The process of creating the Leopold Legacy Center was ultimately about finding real solutions to large-scale problems, about finding hope and a larger sense of community, and about demonstrating what it means to live on a piece of land without spoiling it.

Other Information

The Aldo Leopold Legacy Center was funded largely through the multiyear, $6.9 million "Land Ethic Campaign" capital fundraising effort. In addition to providing construction funds, the Land Ethic Campaign proceeds will help restore and protect the historic Leopold Shack, preserve and maintain the Leopold archives, and establish an endowment fund. The Kresge Foundation provided a $300,000 challenge grant and a $50,000 green building planning grant. The architectural team provided conceptual fundraising materials and gave presentations at donor events.

The Foundation received many generous financial gifts, but it is hard to place a value on the gift of sweat equity given by volunteers to strip bark from Leopold pines. This effort and other acts of generosity contributed to the success of the building. The site-harvested lumber had a market value conservatively estimated at $250,000, more than 70% of the value of all lumber used in the project.

Cost Data

Cost data in U.S. dollars as of date of completion.

-Total project cost (land excluded): $3,943,418

Early detailed cost estimating was essential for the successful integration of the green design concepts and was achieved by engaging the services of a qualified construction manager from the project outset.

During the course of this project, the design team was often asked about the payback period for green features. Economic calculations are necessary for any construction project, but from the outset the Foundation defined payback broadly. The Foundation wanted to take full responsibility for the environmental as well as the economic costs of construction. This distinction cuts to the essence of Leopold’s Land Ethic. Leopold argued that purely economic motives, as they are commonly understood in modern life, were not sufficient to preserve the long-term health and stability of the biotic community. He wrote that “a system of conservation based solely on economic self-interest is hopelessly lopsided. It tends to ignore, and thus eventually eliminate, many elements in the land community that lack commercial value, but that are essential to its healthy functioning.”

The single largest energy investment in this project was the solar photovoltaic system, which cost $240,000. Over its 25-year projected lifetime, the system should produce more than five times the embodied energy used to manufacture it. Simple economic payback is relative to local economic incentives. In this case, the simple payback based on first cost and local electricity rates is 97 years; in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, however, the same system would have a simple payback of 14 years. But in either case the environmental cost is the same. The decision to install the system reflects the Foundation's clear commitment to achieve a net-zero, carbon-neutral building.

Predesign

The goal for this project was to demonstrate how human activity, the built environment, and the natural world are intertwined in a larger cycle of energy and life. Perhaps the most lasting achievement of the Legacy Center will be its strict adherence to a holistic design process consistent with Leopold's understanding of ecological systems, a process that offers the promise of shared benefit for both human inhabitants and the land.

At the project outset, Aldo Leopold’s daughter Nina expressed her desire for a facility that would introduce visitors to a particular quality of understanding. To illustrate her meaning, she described the typical tourist center, which briefly entertains visitors in a “high-volume, low-intensity” experience. Nina's vision, in contrast, was to encourage a “low-volume, high-intensity” experience. She wanted to create a place that would engage visitors more deeply, a place that would afford each individual the means to fully consider what Leopold described as the “Land Ethic.”

The design team took inspiration from the Shack, where Leopold did much of his writing, but did not seek to copy it. Perhaps most influential was Nina’s comment that "the Shack was everything, and it was nothing,” which the architects understood to mean that, while the Shack served as an outpost for the family’s restoration efforts, the physical nature of the building was less important than the work that took place there. The architects concluded that the end-all of the Leopold legacy could never be a building. That approach would quietly emphasize a mechanical solution over ecological wisdom. Thus, the design efforts strove to shift the focus from the buildings themselves to the spaces and the activities associated with them.

Design

The design team balanced new technologies with time-tested strategies. By relying too much on technology, architecture risks losing historic knowledge about how to create comfortable, durable buildings with low-tech, low-energy—but highly intelligent—solutions developed over generations. The Legacy Center was designed to combine both approaches in a beautiful and functional space.

From the start of the schematic design phase through construction, project-team meetings included the environmental consultant, energy-simulation consultant, commissioning agent, and control-system consultant.

Construction

The ambitious nature of this effort required the project team to rethink traditional approaches to design and construction. In typical projects, the architect typically designs without regard to the availability of materials or the impact of their use. Building plans are drawn in isolation, and then a list of component parts—structural elements, flooring, walls, and roofing—are ordered from a factory somewhere and delivered to the construction site for assembly. In its traditional form, architectural design is a linear process with little regard for constraints other than economics or style.

For this project, the team chose another path. The decision to harvest trees planted by the Leopold family presented a complex and inverted design challenge. To put the finite quantity of this precious resource to the best use, the design team had to work backward, matching the building to the available resources. The use of Leopold wood is the most visible, and perhaps the most symbolic, of the team's efforts to design within the resources available on site, including sun, earth, and water. The result was a design process that fully considered the true ecological costs of the materials and resources used for construction as well as those that would be required to operate the building.

Operations/Maintenance

The team designed the building-control systems to include alarms for malfunctions or system operations outside the accepted ranges.

The project's heat pumps, radiant floor pumps, and air-handling units are turned off when staff places the system in natural-ventilation mode. The sequence of operation integrates staff control of systems through a Web-based controls interface. The Foundation has entered into a maintenance contract with mechanical and controls contractors who have online access to the controls system to respond to operational issues and tweak control settings as necessary.

Commissioning

The commissioning agent interviewed all consultants and subcontractors before they were hired to ensure they understood and agreed to work within the requirements of constructing a high-performance building that would meet the highest levels of LEED certification.

The contracting team spent two weeks performing its own systems commissioning in preparation for the commissioning agent’s visit. The commissioning agent will review performance at the end of the first year of occupancy to ensure that systems are performing as designed.

Post-Occupancy

The ongoing monitoring of building systems and performance is a priority. The commissioning agent is currently engaged in measurement and verification, and the environmental consultant agreed to spend the 2008 academic year in residence at the Legacy Center measuring performance and observing staff interaction with the building.

A large number of building and site sensors allow significant data feedback. An on-site weather station; multiple relative humidity, dewpoint, and carbon dioxide sensors; load submeters; and flow meters will allow for subsystem performance evaluation and adjustments. The controls-system consultant developed an archived database of all control and measurement points in the system.

Staff have implemented accounting methods for gasoline use, air travel, and firewood use to provide annual estimates of carbon emissions. The Foundation's staff ecologist will work with the environmental consultant to measure the carbon sequestered in forested lands. Photographs of the forest taken prior to the harvest established a visual baseline, and monitoring points throughout the stands will record changes in forest growth and health over time.

Additional Images

Project Team and Contact Information

| Role on Team | First Name | Last Name | Company | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architect | Allen | Washatko | The Kubala Washatko Architects, Inc. | Cedarburg, WI |

| Architect | Tom | Kubala | The Kubala Washatko Architects, Inc. | Cedarburg, WI |

| Environmental building consultant | Mike | Utzinger | University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Architecture | Milwaukee, WI |

| Owner/developer (Executive director) | Buddy | Huffaker | The Aldo Leopold Foundation, Inc. | Baraboo, WI |

| Ecologist and timber harvesting expert | Steve | Swenson | The Aldo Leopold Foundation, Inc. | Baraboo, WI |

| LEED consultant | Theresa | Lehman | The Boldt Company | Appleton, WI |

| Contractor | The Boldt Company | Appleton, WI | ||

| Commissioning agent | Ron | Perkins | Supersymmetry USA, Inc. | Navasota, TX |

| Energy consultant | David | Bradley | Thermal Energy Systems Specialists, LLC | Madison, WI |

| Carpentry contractor | Fred | Bachmann | Bachmann Construction Co., Inc. | Madison, WI |

| Photovoltaic contractor | Andrew | Bangert | H & H Group, Inc. | Madison, WI |

| Mechanical contractor | Brady | Farrell | H & H Group, Inc. | Madison, WI |

| Electrical contractor | Chip | Plummer | H & H Group, Inc. | Madison, WI |

| System controls consultant | Bob | Hines | Hines & Co., LLC | Winston-Salem, NC |

| Structural engineer | Bob | Gilomen | KompGilomen Engineering, Inc. | Milwaukee, WI |

| Mechanical and plumbing engineer | Bob | Eliopolous | Matrix Mechanical Solutions, LLC | Greenfield, WI |

| Electrical engineer | Tom | Pfefferkorn | Powrtek Engineering, Inc. | Waukesha, WI |

| Plumbing contractor | Mark | Schoeff | Schadde Plumbing & Heating, Inc. | Baraboo, WI |

| Landscape architect | Missy | Inoue | Chicago, IL | |

| Landscape architect | Marcy | Hufaker | The Aldo Leopold Foundation, Inc. | Baraboo, WI |