Heifer International Headquarters

Project Overview

An organization dedicated to alleviating world hunger, Heifer International begins its interaction with communities by delivering one animal to one family. Like a drop of water generates ripples flowing outward from the impact point, the animal creates concentric rings of influence through a village, allowing knowledge and opportunity to be passed to others as the animal's offspring are gifted.

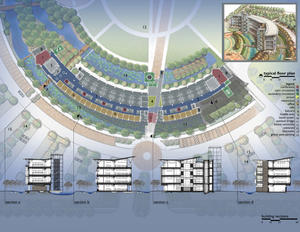

Part of a four-phase master plan, the Headquarters building was conceived as a series of concentric rings expanding from a central commons. The architecture was designed to expand environmental stewardship into the public realm while serving as a beacon of hope.

Design & Innovation

Located next to the Clinton Presidential Library, the Heifer International Headquarters is in walking distance of busses, a new light-rail system, and a pedestrian entertainment district.

A restored wetland that wraps around three sides of the building collects stormwater for reuse as irrigation water. Rainwater collected from the roof is stored in a five-story water tower wrapped with a fire stair. Graywater collected from sinks and drinking fountains, condensate from outside air units, and rainwater from the water tower are reused in the toilets and cooling tower. Moisture removed from the building as condensate is reused to cool the building. Waterless urinals and low-flow toilets and lavatories further reduce potable water use.

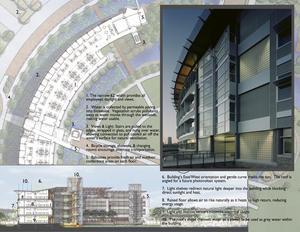

The narrow, semicircular floor plan provides daylight and views for all employees. The majority of open offices in the building offer river views and northern light, and all major gathering spaces access the exterior: five balconies on each floor, designed as outdoor conference rooms, hang over the wetland and act as sunscreens.

The building was designed to use up to 55% less energy than a conventional office building and to last for at least 100 years. Materials were selected for their durability, maintainability, low toxicity, recycled content, and regional availability.

Regional/Community Design

Among the potential project sites, the one selected posed the greatest environmental challenge as well as the greatest opportunity to communicate Heifer's mission to the public.

The site is located directly adjacent to the Clinton Presidential Library, at the terminus of a major avenue. This prominent location allows access to busses, a new light-rail system, and a pedestrian entertainment district. Employees bike, walk, carpool, and even canoe to work. The site also takes advantage of the neighboring building's 30-acre park setting by blurring the property edges, allowing both projects to sit in a combined 60-acre greenbelt.

Land Use & Site Ecology

As an extension of a riverfront park, the Heifer grounds work in harmony with the natural ecology, while paths connect the river environment to the building. Splayed parking areas paved with a permeable surface radiate out from the building with bioswales between the rows, allowing native trees and vegetation to dominate the parking area. The building’s arced shape, wrapped on three sides by the constructed wetland, shields the main pedestrian commons from the cars.

The project sits on a former brownfield site—a railroad switching yard previously bisected the site. Originally, 60% of the 22-acre site was paved. The site is now a thriving ecosystem, however; ducks and other wildlife appeared in the wetland within months of the project's completion.

Bioclimatic Design

The site provided excellent opportunities to take advantage of climatic conditions. From a solar standpoint, a building that stretches from east to west was easily attained; however, further study of the building's position within the concentric ringed master plan offered the opportunity to arc and articulate a layered footprint, allowing more light into the building later in the day. Light modeling confirmed the best arrangement of vertical fins to redirect light, even in late afternoon. The southern facade of the arc is longer, tracking the sun. The northern facade cups the commons, offering a shaded wetland area.

Each elevation is distinct to its orientation. Significant overhangs reduce solar heat gain. Balconies large enough for meetings act as sun control on the east and west ends of the building. A first floor area, completely outdoors, mimics the conference rooms above, offering meetings in the wetland.

To capture prevailing southwestern breezes, each floor's cafe-like open break areas have large sliding doors. Fire stairs are outside the building envelope, floating over the wetland in glass. Open grates with insect screens allow natural convection to pull cooled air off the water to exhaust at the stair top as it heats.

Light & Air

The majority of open offices in the building are positioned to take advantage of river views and northern light. A 62-foot building width and east-west orientation enable natural light to penetrate to each floor’s center, giving all 474 employees access to light and views. Conference rooms anchor the building’s ends, offering views of downtown Little Rock and Heifer's global village exhibits. All major gathering spaces access the exterior: five balconies on each floor, designed as outdoor conference rooms, hang over the wetland and act as sunscreens. Lightshelves, vertical fins, and deep overhangs minimize glare while increasing diffuse light.

To promote indoor air quality, the project team selected materials with low levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Air distribution through a raised access floor offers individual control over thermal conditions. As an alternative to break rooms, each floor’s open café areas offer light, views, community, and exterior access.

Water Cycle

Stormwater is filtered by indigenous plants in bioswales that feed a constructed wetland before being reused for irrigation. Brick preexisting on the site and new gravel paving systems cover 51% of the parking area.

A 30,000 ft2 inverted roof directs rainwater to a five-story, 42,000-gallon water tower wrapped with a glass-enclosed fire stair. Waterless urinals, a city first after much negotiation, and low-flow toilets and lavatories minimize potable water use. Graywater collected from sinks and drinking fountains, condensate from outside air units, and rainwater from the water tower are reused in the toilets and cooling tower. Moisture removed from the building as condensate is reused to cool the building.

Energy Flows & Energy Future

The fundamental goal of the design team was to create integrated building systems that maximized both energy savings and educational potential. Exposing the systems offered an excellent educational opportunity by connecting how the air and water moves with how we move and work.

The building achieved 55% energy savings over a comparable base case, due in large part to the use of daylight as the primary source of ambient light during work hours. The building's east-west axis allows for minimal electric lighting. Dimming systems adjust lighting according to natural light levels, while occupancy sensors manage light for only spaces in use.

Vertical fins and horizontal sunshades limit unwanted solar heat gain while redirecting daylight into the building's interior. Glazing on the building has a U-value of 0.29, and the R-value of the envelope is 25.

Raised floors offer air distribution that naturally rises to high return ducts, minimizing horsepower for fan units, while allowing for higher ceilings and windows.

To maximize and plan for a future photovoltaic system, the roof is angled to receive the most sunlight for the Little Rock solar orientation.

Metrics

Materials & Construction

One of the goals for the project was to use locally sourced materials whenever feasible. A steel structure was chosen because the steel factory was three blocks from the site and the material included 97% recycled content; the heavy timber roof was also sourced locally. An aluminum curtainwall and skin, making up more than 90% of the exterior, was fabricated at a major glass company located directly across the street.

The project team selected durable, low-toxicity materials for the project interior. These included toilet partitions made largely of sawdust, reception and toilet countertops made of recycled glass, and easily reconfigurable, locally manufactured storefront systems. Exposed-steel floor decks were left unpainted, which saved money while maintaining their reflectivity.

Long Life, Loose Fit

The building was designed to be easily maintained and to last for at least 100 years. A raised floor offers individual control of air distribution, and the office systems can be easily reconfigured. Of the building’s 62-foot width, 50 feet consists of flexible, demountable systems, open to northern light. Conference rooms and mechanical rooms are located at each end of the building, allowing open and flexible arrangements on the entire floor in between. This approach allowed the break areas to become open café areas that have become popular for meetings. Huddle spaces for small interactions—designed as demountable wood and glass boxes that reference the design of Heifer’s zero-grazing livestock pens—are located along the circulation path.

Because Heifer is a nonprofit organization that relies on community connections and outreach for funding, the facility and site are open to the public. During the planning process, the project team identified opportunities within the design to educate the public about environmental issues. The light-filled atrium doubles as a vertical gallery where Heifer displays information about both its work and the building's environmental attributes.

Collective Wisdom & Feedback Loops

This design process began with sharing knowledge and goals. It was important that the building speak of its environmental responsibility as well as Heifer’s story. The strongest shared statement came from the founder’s daughter, who remembered her father speaking of village visits where a community would make decisions sitting in a circle, all facing each other as equals. During the Headquarters design process, members of the project team, the community, and the client made collaborative decisions in that same arrangement: all ideas were considered equally worthy of consideration.

The integrated design approach focused on actual, not perceived, measures of environmental responsibility, meaning that the anticipated environmental results drove the design and that beauty was found in those features.

This design approach did offer challenges. The process required additional time and effort from a design standpoint. In construction, early site and steel packages hindered efforts to fully integrate the design. The project was very successful, however, in its introduction of new thinking into the construction industry, opening the door for future local projects to take advantage of the lessons learned here.

Other Information

Through the integrated design process, the project team was able to participate in early discussions ranging from methods of finance to site selection. Heifer had grown rapidly over recent years and was renting two full floors of a downtown high-rise as well as space in two other buildings. An analysis of rent expenditure showed that an equal amount would be spent on an ownership payment, and Heifer chose to finance the project through a combination of conventional loans and a capital campaign.

A grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency financed brownfield cleanup.

Heifer purchased eight individual land tracks and allowed the city to build a perimeter road to alleviate congestion from the adjacent project. This opened new access to the site and will provide for the use of adjacent City land for future Heifer projects.

Financing Mechanisms

-Grant: Public agency

-Loans: Private (bank, insurance)

Cost Data

Cost data in U.S. dollars as of date of completion.

-Total project cost (land excluded): $17,900,000

Because of the tight budget, the design team performed life-cycle cost analyses for major systems and tested every idea against Heifer’s ideology. For any cost that would not be part of a conventional office building, the team used a payback period of seven to ten years as a baseline to determine its viability. For example, vehicle recharging stations, while environmentally responsible, would get very little use and were not projected to meet the acceptable payback period. This analysis encouraged the project team to pursue inexpensive means of encouraging alternative transportation, such as providing preferred parking for hybrid vehicles and connections to public transportation.

Predesign

Initial sketches showed a building that was 40% smaller than the final result, on roughly half the amount of land. Because of tremendous increases in donations and staff and a desire to increase the potential for educational exhibits, however, Heifer revised its projected growth figures, and the project team determined that the project and site needed to be larger. At the same time, the team reassessed its environmental goals to allow the building to more accurately reflect the aspirations of Heifer.

An open dialogue began with a goal-setting charrette that included all consultants and a large Heifer contingent. The participants determined that the project parameters had changed to the point that the initial design was no longer viable, opening a process that led to the final design. From this process, the team established a list of attainable environmental goals.

The project team participated in monthly environmental committee meetings to better comprehend the organization's core mission and identify specific educational opportunities within the design. The team's efforts to create an energy-efficient design were geared toward freeing up funding from the infrastructure for use in promoting programs around the world.

Design

To formulate the structural concept for the building, the project team studied how Heifer would build around the world. The simple elegance of these structures—including just what is needed—led to a goal to minimize the ornamentation common in this building type and to express the functional detailing of the steel in a beautiful way.

The project team wanted the structure to sit lightly on the land, which led to the creation of thin planes at floor edges and the roof. Each tree column was designed as one tube, four stories tall, capped with light, fingerlike tube branches. All systems were integrated and visually cupped within the fingers of the trees. The inverted roof was designed to direct rainwater to exposed pipes above circulation paths. Extended steel beams at the roof edge were capped with galvanized steel grates to extend the sun protection and lighten the edge in a crown-like fashion.

The lobby hosts a sculptural building-section model with interactive displays that highlight the Headquarters' green attributes, such as the rainwater collection system and the lightshelves, and explain how they are connected to Heifer’s work.

Construction

The design team felt that it was important to get buy-in from the construction team to ensure the best and clearest translation from the design to reality. The design team held numerous meetings with the construction team in an effort to communicate not only the process of documenting LEED criteria but also the larger picture. The contractors researched and submitted many alternate materials to ensure compliance with indoor environmental quality needs and local availability. Many vendors and suppliers showcased and promoted products that were being used for the first time in this market. The team reviewed LEED criteria and submittals during each weekly construction meeting.

Operations/Maintenance

Long-term operations and maintenance were critical considerations in the selection of materials and systems. The office building was designed for a 100-year life with normal replacement of items at anticipated intervals. Exterior and interior materials were selected for their durability and low maintenance needs. Mechanical systems and lighting systems, while complicated due to the level of control and reporting required for LEED, were supplied with user-friendly interfaces.

Commissioning

A commissioning agent was involved in every aspect of the design process. The agent provided peer review and input during each phase of the project, produced a commissioning plan, attended construction update meetings, and performed all the required commissioning duties during the installation, testing, and acceptance of the identified and required systems and equipment. The same agent was hired to monitor and report on the building's performance during the first year of occupancy.

Additional Images

Project Team and Contact Information

| Role on Team | First Name | Last Name | Company | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architect (Construction administrator) | David | Porter, AIA | Polk Stanley Rowland Curzon Porter Architects, Ltd. | Little Rock, AR |

| Architect (Project coordinator) | Ed | Sergeant | Polk Stanley Rowland Curzon Porter Architects, Ltd. | Little Rock, AR |

| Architect | Dustin | Davis, Assoc. AIA | Polk Stanley Rowland Curzon Porter Architects, Ltd. | Little Rock, AR |

| Landscape architect | Martin | Smith | Larson Burns Smith | Little Rock, AR |

| Interior designer | Korie | Caldwell | Polk Stanley Rowland Curzon Porter Architects, Ltd. | Little Rock, AR |

| Civil engineer | Dan | Beraneck | McClelland Consulting Engineers, Inc. | Little Rock, AR |

| Mechanical engineer | Todd | Kuhn | Cromwell Architects Engineers, Inc. | Little Rock, AR |

| Structural engineer | Joe | Hilliard | Cromwell Architects Engineers, Inc. | Little Rock, AR |

| Electrical engineer | Pam | Fligor | Cromwell Architects Engineers, Inc. | Little Rock, AR |

| Environmental building consultant | Bradley | Nies | Environmental building consultant | Kansas City, MO |

| Commissioning agent | Hamid | Habibi, P.E. | TME, Inc. | Little Rock, AR |

| Contractor | Danny | Bennett | CDI Contractors, LLC | Little Rock, AR |

| Owner/developer | Tanya | Wright | Heifer International | Little Rock, AR |

| Director of facilities management | Erik | Swindle | Heifer International | Little Rock, AR |

| Hazardous materials consultant | Ann | Woker | Ecologic, Inc. | Little Rock, AR |